As the Taliban take Afghanistan, should we worry about the return of al Qaeda, ISIS and international terrorism?

A sad departure from Kabul in 2021 does not necessarily mean another attack like September 11, 2001

News from Afghanistan is sad, the footage tragic, as the Taliban have retaken the nation’s capital Kabul just less than 20 years before their violent removal by U.S. forces in response to the September 11, 2001 al Qaeda attacks on America. Naturally, fears of al Qaeda’s return and ensuing waves of international terrorism have quickly cropped up given the Taliban’s return. The enduring responses and doomsday predictions of the counterterrorism punditry era have quickly arisen, too—a victory for jihadis, the return of a safe haven for al Qaeda, which is a shadow of what it was in 2001, and the annual charge that al Qaeda would be making a comeback … for the twentieth straight year.

Well, since U.S. and Iraqi forces ushered the Islamic State out of Mosul, there’s not been much for jihadists to cheer about. Despite some public claims of an “intelligence failure” (it was not) or “shocked” by the rapid Taliban takeover when U.S. forces left: For many, we always assumed this is where the conflict would likely end. The U.S. military was not defeated in Afghanistan, we decided to leave, and when we did leave, it would not be pretty.

Fear mongering over a coming international terrorism boom feels tired after two decades of such claims, and we now have an entire generation of terrorism and counterterrorism expertise to more rationally evaluate the likelihood of al Qaeda and/or ISIS, or one of their spawn rapidly growing inside Afghanistan in the near future. I’d also note the consensus thinking in the last decade has led to many predictions that turned out incorrect: al Qaeda broke into factions despite many saying it would never happen, ISIS did not quickly rebound when U.S. forces again began leaving Syria and Iraq, and Iran did not initiate a major war with the U.S. after the assassination of General Qasem Soleimani. Conventional wisdom failed and instead here at this blog, we prefer selected wisdom from specialists which I will link to throughout this discussion.

In short, I don’t know nor do I believe most anyone else knows what direction international terrorism will take with the Taliban back in control for merely a week. But several factors should be evaluated, for much has changed in the last 20 years in Afghanistan for both terrorists and those fighting them.

Why did the Taliban harbor al Qaeda in 2001 and would they harbor al Qaeda in 2021?

Several ingredients came together in the terrorism recipe that led to the devastating attacks on September 11, 2001, and here’s a recap of what would normally encompass a book. Ten years earlier, in 1991, Osama Bin Laden transformed his mujahideen cadres into an international ideological indoctrination and military training center called The Base (“al Qaeda” in Arabic), first in Sudan and later in the Taliban safe haven of Afghanistan. Bin Laden’s trainees meddled in Yemen, Somalia, and Bosnia with limited effect, and struggled to find their place in international jihad until Ayman al-Zawahiri fled Egypt and joined Bin Laden in Afghanistan issuing a fatwa against American in 1998. Bin Laden called for attacks on the United States, the far enemy, which he and al Qaeda believed propped up the near enemy, apostate dictators across North Africa and the Middle East. The U.S. presence in the Muslim holy lands of Saudi Arabia and American support for Israel provided the ideological justification for far-reaching terrorist attacks in the U.S. homeland. The Taliban provided safe harbor for Bin Laden and al Qaeda’s global ambitions, a decision that ultimately cost them their Islamic emirate in 2001.

In the near future, we can expect the Taliban will naturally turn to its old ways incrementally restoring its backward militant belief system. The Taliban, out of loyalty and kinship, still does and will likely continue to allow for the return of some al Qaeda operatives stowed away in neighboring states of Pakistan and Iran and some jihadi refugees from the Middle East. But why would the Taliban, again, allow an al Qaeda, an Islamic State, or some other spawn of the jihadist movement to plot, plan, and attack the U.S. from inside Afghanistan? Certainly twenty years of conflict has created deep seated resentment and possibly the motivation for terrorist attacks against Americans. But would such attacks motivated by revenge be worth the potential demise of their Islamic emirate once again? As seen before September 11, 2001 and what we’ll likely see after September 11, 2021 is that the West will let the Taliban have its medieval Islamic emirate as long as it doesn’t produce global terror attacks. The larger question is ...

Will Afghanistan, again, become a global safe haven for terrorist groups?

The Taliban offered safe haven to al Qaeda 20 years ago and they were, for the most part, just as surprised as anyone else when Bin Laden and company destroyed the World Trade Center. A broader question about Afghanistan comes down to whether terrorist groups will again use it for a safe haven even if the Taliban would prefer their turf not be used to launch international terror attacks.

We’ve already seen some of the misguided “we fought them over there, so they didn’t attack us here” jargon resurfacing in U.S. media. While that tough talk may have worked in domestic political settings, in reality, America’s interventions into Afghanistan and Iraq created more extremists “there” (in the Middle East and South Asia) and “here” (inspired homegrown violent extremists radicalized remotely on the Internet). This claim is also ridiculous because there have been terrorist groups operating in Afghanistan and neighboring Pakistan the entire time the U.S. was in Afghanistan. The Islamic State, for example, set up an affiliate in Afghanistan while U.S. troops were in Afghanistan.

The idea that al Qaeda will rapidly set up shop back in Afghanistan and then immediately launch attacks against the U.S. is the laziest analytical argument I’ve seen so far this week. First, the U.S. has not abandoned all of its counterterrorism and intelligence capabilities in Afghanistan or globally, and this time around we’d be better positioned to detect and disrupt an upcoming jihadist surge. Sure, the rapid withdrawal has damaged American intelligence coverage, but it hasn’t entirely evaporated. Second, there are many terrorist safe havens around the world today that jihadists can plot and plan from if they choose. Al Qaeda went to Afghanistan out of necessity in the 1990s, not so much by choice, having been rejected by the Saudis and needing to head out of Sudan. Al Qaeda, the Islamic State or other jihadi groups don’t have to reorganize in the far off hills of Asia when most jihadis have deeper sentimental ties to Islam’s historical home in Arabia. Finally, al Qaeda today is not the al Qaeda of 2001. (For more on the Afghanistan safe haven question, see this excellent piece by Dan Byman in Foreign Affairs.)

Al Qaeda then and now: From lead dog to somewhere in the pack

For 20 years, it’s been standard boilerplate to make fearful claims about an al Qaeda resurgence. Each year it's been more difficult to know who is even in al Qaeda, who is in charge, and what they intend to do. Afghanistan hosts not one, but many terrorist groups. Al Qaeda, the Islamic State, and others must compete with each other for manpower, resources and operational space. Each of these extremist enclaves will seek to carve out their niche, appeal to locals, and set themselves apart. Competition will be the norm more than cooperation, with some terrorist groups expending lots of energy focused on other extremists rather than the U.S. (For more on these dynamics of terrorist competition, see here.) Meanwhile, other smaller outfits might seek to go big with a 9/11 style attack to bolster their image. In short, jihadi groups abound in the region and simply yelling “al Qaeda” paints over a dynamic and complex network of affiliates and splinters.

Terrorist groups in Afghanistan also have different motivations and resulting far enemies. Often forgot in Afghanistan terrorism discussions is the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and other associated groups that could make the north of Afghanistan another Chechnya for Russia. The early days of U.S. invasion brought an odd number of Uighur Muslims from Afghanistan and Pakistan to Guantanamo Bay. Today, the Uighur population in China resides in mass detention. Jihadist extremists likely have more than the U.S. in their crosshairs and many nations closer to home they might attack.

Technology matters: In 2001, many Afghan homes didn’t have a radio. In 2021, most have cell phones.

On September 11, 2001, I served as the commander of an infantry company of 3rd Brigade, Second Infantry Division, at Fort Lewis, Washington. In the weeks and months following the attack, we clamored for information about Afghanistan and there wasn’t much to be found. Low-quality paper maps were printed as quickly as they could be found. I read the two to three books available on the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and a small handful of websites that had info. I later learned that the CIA worked to track Bin Laden and al Qaeda and even used an unmanned drone to locate him. During my studies, I learned that only a portion of the country’s homes had radios as of the U.S. invasion.

Twenty years later, Afghanistan has been mapped geographically, culturally, or technologically by nearly every arm of the U.S. government and NGO community. Even for the public, today, one can go to Snapchat’s live view and watch chaos at the Kabul Airport and surprisingly calm in other parts of the city. The Taliban has technology too, and can network in and outside the country with other extremists—the capability goes both ways. In sum, the U.S. has much greater tech capability and understanding today as compared to the Taliban, but in counterterrorism, America has to be correct every time, and the Taliban and any terrorists they harbor only have to be successful once. It’s hard to know who has the advantage and of course this leads to a debate over social media.

Should we worry about the Taliban on social media?

The second phase of terrorism hype kicked in on Wednesday with the revelation that the Taliban has social media accounts on Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. The Taliban, not designated a foreign terrorist organization by the U.S. State Department but on the sanctioned OFAC listing at U.S. Treasury, is more difficult to police in part because their accounts are normally not violating terms of service with violent content. YouTube and Facebook closed some of their official accounts, but those that remain on Twitter operate more like those of an official state than al Qaeda or the Islamic State. Their content is … boring, and doesn’t draw that much audience, that was until U.S. newspaper started making a fuss about them. Their dull content is not generating the type of fanboy support and user-generated assistance that we’ve seen from major social media surges from jihadists after attacks in Paris or Brussels, young jihadists want the violence, not the policy negotiations. Overlooked in the Taliban social media panic articles is the issue of language. Most of the Taliban’s remaining official accounts, aside from being lame, broadcast in Pashtun with only a sprinkling of them offering Arabic or English content accessible for the broader jihadist community. At present, I’m not too concerned about the hype regarding Taliban media operations.

What should we look for to determine whether there’s a coming jihadi terrorism resurgence resurgence? (i.e. al Qaeda, ISIS or whatever comes next?)

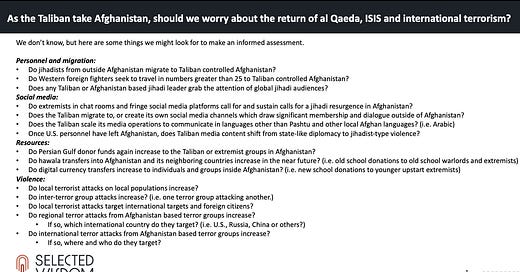

Please don’t take the above as a suggestion that we should not worry. We should be concerned about our counterterrorism capability and that Afghanistan will again become a safe for international terrorism. The truth as of today, though, is we don’t know. There’s been a major change in the global terrorism ecosystem, and rather than make hyperbolic or vague claims about the risk (i.e. medium) and timeline (i.e. two years) of future terrorist threats from Afghanistan, we could establish indicators to understand whether and when we could be concerned about terrorist threats resurging from a historical homeland. Here’s a short, incomplete listing of indicators I’ll be looking for in the coming weeks and months

Personnel and migration:

Do jihadists from outside Afghanistan migrate to Taliban controlled Afghanistan?

Do Western foreign fighters seek to travel in numbers greater than 25 to Taliban controlled Afghanistan?

Does any Taliban or Afghanistan based jihadi leader grab the attention of global jihadi audiences?

In mainstream media?

In social media?

Social media:

Do extremists in chat rooms and fringe social media platforms call for and sustain calls for a jihadi resurgence in Afghanistan?

Do any of the individuals and associated accounts calling for global jihad in Afghanistan actually make the move to Afghanistan?

Does the Taliban migrate to, or create its own social media channels which draw significant membership and dialogue outside of Afghanistan?

Does the Taliban scale its media operations to communicate in languages other than Pashtu and other local Afghan languages? (i.e. Arabic)

Once U.S. personnel have left Afghanistan, does Taliban media content shift from state-like diplomacy to jihadist-type violence?

Resources:

Do Persian Gulf donor funds again increase to the Taliban or extremist groups in Afghanistan?

Do hawala transfers into Afghanistan and its neighboring countries increase in the near future? (i.e. old school donations to old school warlords and extremists)

Do digital currency transfers increase to individuals and groups inside Afghanistan? (i.e. new school donations to younger upstart extremists)

Violence:

Do local terrorist attacks on local populations increase?

Do inter-terror group attacks increase? (i.e. one terror group attacking another.)

Do local terrorist attacks target international targets and foreign citizens?

Do regional terror attacks from Afghanistan based terror groups increase?

If so, which international country do they target? (i.e. U.S., Russia, China or others?)

Do international terror attacks from Afghanistan based terror groups increase?

If so, where and who do they target?

Lastly, once U.S. citizens and associated evacuations have been completed, does the U.S. designate the Afghan Taliban a foreign terrorist group? This will be a tricky call, and such a designation may ultimately be counter productive as the Taliban will control a state that may then be incentivized to harbor and cultivate jihadi terror groups.

In conclusion, we should worry about an international terrorism resurgence, but I’d remind every American that we’re only a few months after a violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol and yesterday a man from North Carolina shut down Capitol Hill for hours with a bomb threat. Someone in the U.S. is more likely to be killed by COVID-19 than a terrorist, and more likely to be killed by a domestic terrorist living in one’s neighborhood than an international terrorist residing in the remote mountains of Afghanistan. Let’s keep some perspective.

"safe havens" are not necessary to plot terror attacks. Nor are training camps. The only tool you need to plot ANYTHING is an internet connection. How is that lost here my friend?

Great stuff as always Weez!